Guest Author

This account is reserved for our Guest Authors and Collaborators.

MORE ABOUT THIS AUTHOR

Jesús leapt from the smooth pavement onto the rubble-strewn field of a former steel mill. Small trolley tracks criss-crossed the disintegrating pavement and a rhythmic slop-slop of lake water echoed in the corrugated metal dock.

Image: “I remember my father when he would hear the ore boats in the [dock], he would always say, ‘That’s the sound of money.’” Jesús, 51, Chicago

Pointing towards the vast horizons of Lake Michigan, he said, “I remember my father when he would hear the ore boats in the [dock], he would always say, ‘That’s the sound of money.’” We both took a breath in, listening carefully to the complete silence. Today, in the southern-most neighbourhood of Chicago, we hear nothing but the absence of hundreds of trains and ships and trucks moving across acres of steel mill properties. Deindustrialisation emptied this urban neighbourhood of tens of thousands of jobs from five local steel mills. Here in Chicago, and in a former iron mining county in Wisconsin, I explored how and why local people frequently leveraged stories about unmaintained infrastructures.

I am a sociologist and a qualitative researcher. Over two years, I observed everyday interactions, conducted nearly 100 interviews, and collected records from local historical archives in these two comparison cases in the former American industrial corridor. While my focus was broadly post-industrial community life, I began to notice how interviewees repeatedly directed our open-ended interviews and field work activities to the topic of industrial transportation infrastructure decline. Unprompted, one in every three interviewees discussed, pointed to maps, or physically took me to disappeared railway tracks and murky industrial canals. I came to realise that making sense of infrastructural decline and how my interviewees interpreted their own histories was necessary for understanding the rationales and concerns of those residents who have remained long-term in deindustrialised communities.

Historical records demonstrated that when these two communities were first founded, train and shipping routes were vital technologies for economic growth and expansion.

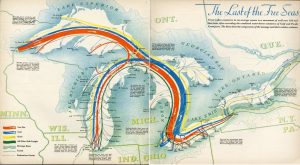

Image: “The Last of the Free Seas, 1934.” Tracing commodity chain connections across the Great Lakes

In Wisconsin, the highest-earning railway in the late nineteenth century leased rights of way from the state to transport iron ore to its Lake Superior docks. Ships then took ore to waterways in cities, like Chicago’s sluggish Calumet River, which only functioned because the city and companies regularly dredged and widened it for industrial purposes. These flows and interconnections represented a web of economic processes linking material objects across space and time. And yet this web required nodes grounded in geographical locations – like south-east Chicago and northern Wisconsin. In short, industrial communities existed only because of iron and steel; iron and steel existed only because infrastructures connected vast sets of resources across the American Midwest.

This geographical foundation for industrial flows anchors contemporary interpretations of loss from long-term residents. When iron and steel companies shuttered in the late 20th century, they, their subcontractors and their political collaborators either reclaimed infrastructural components such as pulleys, railway sleepers or tugboats to repurpose them elsewhere, or abandoned these components to environmental decay or scrap-metal scavengers. The noise and flows of industrial infrastructures contrasted sharply with the silence of closures. In the case of remote iron mining, for instance, Gary told me, “My earliest recollections were of the ore trains going through. …The ore trains just ran and ran and ran, throughout the night.” When mine closures caused the train companies to pull up the tracks, Gary recalled his father declaring that with that, their home town “was dead”.

Narratives of the silence of industrial infrastructures centred the role of deindustrialisation in local lore, not only as a singular event but as a prolonged season of disinvestment. Infrastructure loss or lack of maintenance meant that company closures were only the start of local economic problems. Without rail and with only two two-lane highways connecting the iron mining county to larger cities in the state, my rural interviewees viewed the lack of transportation as both a structural and a symbolic cause of the county’s prolonged economic depression. Richard argued, “If we could get some people interested in entrepreneurship, maybe they could come back here and start something…[but] we’re too far away from where they sell the products. They took the railroads out.” He paused and smiled tight-lipped. “It’s a great place to live, a little challenge to make a living.” Merely through gesturing to part of a transportation system that no longer “makes sense”, speakers conjured up their reality of disinvestment and political abandonment.

Image: “We’re too far away from where they sell the products. They took the railroads out.” Richard, 63, Wisconsin

Like in Wisconsin, the breakdown of south-east Chicago’s waterway represented not only the abandonment of maintenance by both capital and government but the marginalisation of the neighbourhood from the larger city. Without significant industry, freight trains and trucking, like shipping traffic, are few and far between. Residential transportation is also diminished – light rail lines skirt the region, bus lines have decreased, with some bus stops more than a mile from parts of the neighbourhood, and an interstate highway lifts drivers from other parts of the city over the old steel neighbourhoods. With transportation moving people over and around the open lands and waterways unusable for both new large-scale industries and recreation, there are few reasons for Chicagoans to incorporate this neighbourhood into their mental maps. Julie, a volunteer at the local historical museum, declared in exasperation: “People say to me, ‘You live on the southeast side of Chicago? That’s the lake!’” The breakdown of the system represented not only the dissolution of public-private partnerships and the erasure of possible reinvestment opportunities, but also the utter lack of control that people could claim over this portion of the deindustrialisation process.

Infrastructures are symbolic objects, representing the ghosts of entangled economic structures past. Thus, even in their absence – perhaps because of their absence – they are important tools for people to use to define social problems in post-industrial landscapes. Interviews like the ones I conducted in the American Midwest demonstrate the rich, interpretive durability of infrastructures. Even beyond their lifespans and long after maintenance is even possible, sites of industrial transportation residues offer speakers narrative props to link the past with their community’s forward-looking needs. Through these stories, they show how infrastructural problems have created material consequences for future development – problems that can only be solved through another round of top-down economic and political reinvestment.