Guest Author

This account is reserved for our Guest Authors and Collaborators.

MORE ABOUT THIS AUTHOR

This is a guest article by Sandra Gratwohl, based on her presentation with the Driburger Kreis on the larger topic of “Ersatz” (Substitute) in September 2021.

How is one standard of care in medicine replaced with another? Who is allowed to take such a decision? And what are the consequences for patients?

These questions can be asked in relation to the development of maternal-fetal surgery for spina bifida. If this fetal neural tube malformation is detected by ultrasound, maternal-fetal surgery has been available to pregnant women in Switzerland as an option since 2010. This technique, which involves opening the pregnant woman’s abdomen and uterus, does not offer a cure for spina bifida; the aim is to stop the development of the malformation. What makes the situation particularly complex is that the procedure is performed on “healthy” women, since the fetus is the target of the intervention. Pregnant women still have two other options to choose from: termination of pregnancy and postnatal surgery.

Since the publication of the MOMS trial results [1], the in utero procedure has been accepted as the novel standard of care [2]. This development of a new standard can be seen as a linear story of progress: the innovation functions primarily as a techno-optimistic replacement for postnatal surgery. Another story can be told with an ecological-relational approach, where ambivalences, negotiations and partial perspectives come into focus [3]. Here, the relevance of a simple replacement narrative may be called into question.

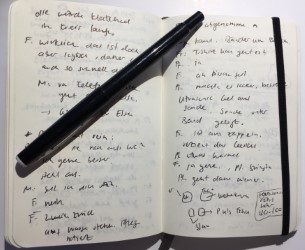

In my thesis, I adopt such an ecological-relational approach, which shifts the focus to the newly produced realities of this process [4]. Indeed, new standards transform existing realities: certain voices are cultivated, while others are marginalised. Invisibilities arise. Postnatal surgical technology has not (yet) been completely replaced by prenatal surgery – perhaps it never will be. At present, the situation is developing in such a way that postnatal surgery is being transformed into a non-option in some cases. The nature of these lived realities in which pregnant women find themselves cannot be elucidated from a desk. As an ethnographer, equipped with a notebook and pen, I have to go to the places where this change is occurring: I have to enter the field of maternal-fetal surgery for spina bifida.

[1] Adzick, N. Scott, Elizabeth A. Thom, Catherine Y. Spong, John W. Brock, Pamela K. Burrows, Mark P. Johnson, Lori J. Howell et al. 2011. “A Randomized Trial of Prenatal versus Postnatal Repair of Myelomeningocele”. New England Journal of Medicine 364 (11): 993–1004.

[2] Meuli, Martin and Ueli Moehrlen. 2014. “Fetal Surgery for Myelomeningocele Is Effective: A Critical Look at the Whys”. Pediatric Surgery International 30 (7): 689–97.

[3] See e.g. Star, Susan Leigh (ed.). 1995. Ecologies of Knowledge: Work and Politics in Science and Technology. SUNY Series in Science, Technology, and Society. Albany: State University of New York Press.

[4] See my SNF Doc.CH doctoral thesis (URL: https://p3.snf.ch/project-184369, 2021.10.13).

Sandra Gratwohl, Ph.D. Researcher Scholar, SNF Doc. CH